Taylor DeSilva

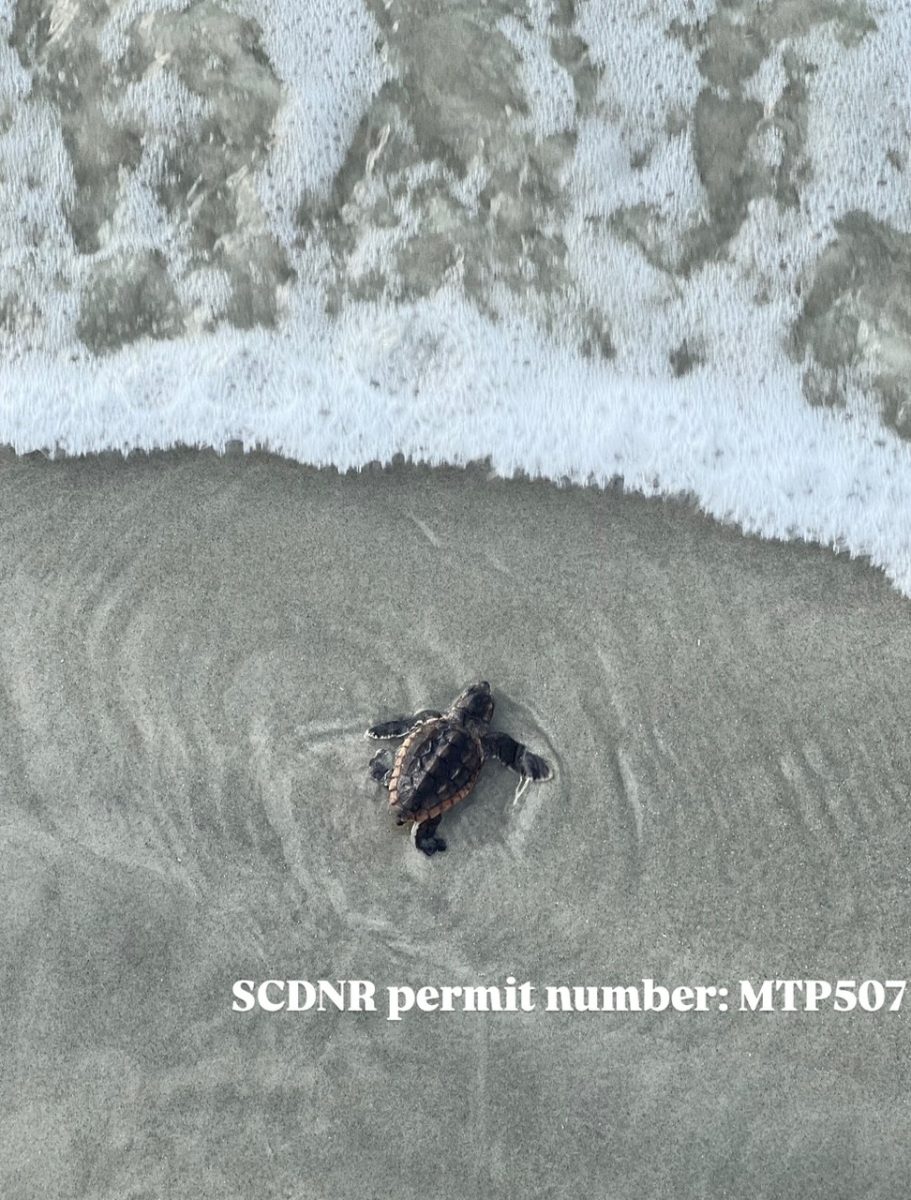

Loggerhead turtle hatchling makes its way to the ocean.

In Georgia, there are multiple species of turtles but one of the most recognizable is the loggerhead sea turtle. They can be found in many parts of the world but the local populations find home in the barrier islands.

July to October is the primary loggerhead sea turtle hatching season, with the nesting season starting in May and ending around late August. Incubation period is about 50-60 days before they hatch and loggerheads can then live up to 80 years.

“The baby sea turtles hatching now are going to outlive me,” said Taylor DeSilva, senior at University of South Carolina-Beaufort, honors Biology major with a concentration in marine biology. DeSilva is a second year Sea Turtle Intern through USCB, team lead on Little Capers island, monitoring the beach and data collecting under a permit.

When the loggerhead clutch is laid, the temperature of the sand determines the sex of the offspring. In cooler sand, the clutch will produce male offspring, with warmer sands being female.

This can produce concerns when it comes to climate change.

“If the temperatures are warming up, does that mean we’re going to get majority females so then there won’t be enough males to repopulate? That’s kind of a big question right now that is concerning.” DeSilva said.

These animal populations are facing threats to their population and livelihood. Loggerheads are listed as both threatened and endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

“Conservation is always a good thing, we have seen numbers in the population rise.”- Taylor DeSilva, Senior at University of South Carolina-Beaufort, honors Biology major with a concentration in marine biology

The biggest threat they are facing today is by-catch, which is unintended catching through fishing. Loggerheads hatchlings are also facing problems with artificial light. Their instincts are to follow light to the ocean but with more infrastructure being built in coastal areas the new hatchlings are trying to follow the light away from the ocean.

An important part of conservation is monitoring and education. DeSilva collects data and genetic samples and puts the information in a database. She also assists live hatchlings.

“The first time I saw a live baby was just magical. It really puts it into perspective, like “oh this is why I’m out here, this is why I’m doing it, it’s for them, to help them.” said DeSilva.

Recent hurricanes have brought in high tides for many coastal towns, islands are facing beach erosion, causing some nests to be taken out to sea. With the program she is a part of, they work on the islands moving clutches to safer zones for a higher chance of survival.

“We have definitely seen a good impact on population, and just survival in general.” DeSilva said.

One of the best ways to help the ocean and loggerheads is the cliche answer, recycle.

“Try to reduce single use plastic. A lot of the times when we’re out on the beach we see a lot of trash, and a lot of it is plastic,” said DeSilva.

Many common items, bags, water bottles and balloons end up in the ocean.

“They’re a magnificent species and an awesome animal, and I would hate to see them suffer at the hands of man made threats like by-catch, pollution and artificial light. I hope, for their sake, that we can do better and conserve them enough to see a steady rise in the populations.”- Taylor DeSilva, Senior at University of South Carolina-Beaufort, honors Biology major with a concentration in marine biology

Loggerheads work with the ocean ecosystem, recycling important nutrients and keeping the ocean floor sediments imbalance. Loggerhead turtles have a unique biological feature, a built-in magnetic map for navigation.

“They are exceptional navigators. They use earth’s magnetic field to guide them on trans-oceanic adventures or migrations,” said DeSilva. This is an inherited trait for hatchlings as well as a homing instinct to the beaches they hatch on.

Georgia’s Coastlines offer opportunities to volunteer, many in Tybee Island and Jekyll Island.

“If you’re interested in getting involved, look into local volunteer networks in the area, you’d be surprised, there’s a lot. Do your part, reduce, reuse, recycle. Don’t be the person that lets out balloons into the wild because those do make it into the oceans,” said DeSilva.