On a clear Dahlonega night, University of North Georgia junior astrophysics major Heath Dobson can usually be found at the North Georgia Astronomical Observatory, pointing his telescope-mounted camera toward the stars.

“Space has been a part of my life for probably all of it,” says Dobson. “I remember when I was a little kid, looking through the space encyclopedia and seeing all the photos, thinking, ‘Oh, that’s just for professional observatories and professional telescopes like Hubble. I’ll never be able to do that on my own.’”

Today, at 20-years-old, he does exactly that.

“It’s an expensive hobby,” says Dobson, who owns all of his astrophotography equipment. “You can make it as cheap as you can, but eventually, to get better results, you’re going to need more expensive equipment.”

He appraises his primary telescope at over $10,000, explaining that even entry-level models rarely sell for less than $1,000.

“I have a well-paying summer job, and I get support from my parents. I’m not afraid to say that,” he says, adding that his passion for astronomy runs in the family. “My dad has kind of an interest in it, but my mother was actually a physics major. They both met at Space Camp in Huntsville, Alabama, back in the ‘80s, so I like to think it was inevitable that one of [their kids] was going to go down this road.”

Dobson didn’t always see himself as an astronomer, though.

“I originally wanted to go into architecture,” he says. “It wasn’t until…I actually started doing astrophotography [at 18-years-old] that I was like, maybe not. Maybe I want to do this as a career.”

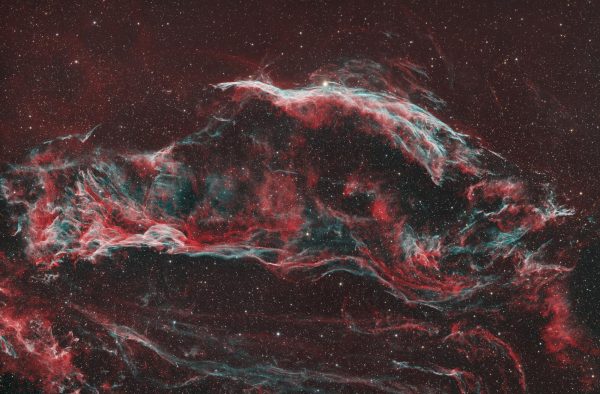

Dobson describes his astrophotography as an “artistic form of expression,” although he says he tries to keep his photos as scientifically accurate as possible.

To take his most recent photo of the Sadr Region, he gathered data for more than 16 hours. Using a monochrome camera, he collected dozens of black and white exposures through different filters to build a final colored image.

“Basically just every night I could image, I took individual exposures [throughout] the night,” he explains. “For example, one of the filters to get a color image on this project was 35 individual exposures. So I first take the exposures, then I go in and combine all the photos from each filter. Then I get a combined monochrome image.”

He uses the astrophotography software PixInsight, which he describes as “one of the best out there,” to combine the exposures and process them, assigning each filter to a red, green or blue color channel.

“I have a filter that collects the entire visible light spectrum, and I use that one for boosting dim signals and cleaning up the image, but that one, I really only use if it’s a broadband physical spectrum image,” he adds. “I also have three narrowband filters, which I use to isolate different sections of the visible spectrum.”

“If I want to isolate a specific gas in space – for this project I used my sulfur, hydrogen and oxygen filters – I order them from longest to shortest wavelength since it’s a false color pallet. So that’s why there’s oranges and blues and greens in that photo,” he says. “Typically, space is pretty red, since hydrogen is the most abundant element and it glows in that red color.”

According to Dobson, the stacked image looks like a black rectangle until he stretches the data to reveal the colors.

“Some data is really easy to work with, and I can get it done in under an hour,” he says. “With this most recent [photo], it was seven hours total processing.”

Because Dobson takes the time to keep his astrophotography scientifically accurate, his photos have been used for more than just aesthetic purposes.

“I used the data from [one of my images] in one of my astronomy classes,” he explains. “We were doing what we call photometry, where we’re measuring the brightness of a star over time. Using that [data], I was able to get a pretty good period on an eclipsing binary, seeing as one star passed in front of the other.”

Director of the North Georgia Astronomical Observatory Gregory Feiden says Dobson’s images are most often used for public outreach.

“It’s easy to sort of inspire people and show them the wonders of the cosmos by literally just showing them the wonderful things that are out there,” says Feiden. “We can tell people all about [those things], but until…[they] sit down and sort of interact visually with the medium, it’s sometimes just abstract and not actually meaningful to a lot of people.”

According to Feiden, Dobson’s photos are often used during the observatory’s free, public telescope viewings to “get people excited about the things they might learn about that night, the things they might see with their eyes or the stuff they can’t see with their eyes but can with a really good camera.”

Although Dobson is one of only three students doing astrophotography from the observatory, Feiden says the activity is accessible to anyone.

“To do astrophotography, in principle, all you need is a nice, digital camera,” he says. “Any student can [rent] a DSLR camera from the library. At the observatory, we are usually quite amenable to people who want to mount their camera to a telescope. We have mounts for most major DSLR cameras.”

In practice, however, he and Dobson agree that astrophotography is a bit more complicated.

“The main difficulty is clouds,” says Dobson. “Also, if you don’t have any automation on your telescope, you’re going to be up all night.”

“Telescopes are very sensitive to movement. I think the hardest part is just finding a place that’s dark enough to do it, getting as much data as you can, but then also having equipment that can…keep your stars nice and sharp, and nothing gets blurry from tracking mishaps.”

“There is [also] a lack of sleep from weather anxiety,” he continues. “A few nights ago, I had to actually race out to the observatory to cover up [my telescope and camera] from a pop-up rain shower.”

Despite the challenges, Dobson is working hard to perfect his craft.

“I’m still learning as I go along, and it’s not just the data capture that’s difficult, it’s also processing the data,” he says. “That’s something I’m still learning to this day.”

To view Dobson’s astrophotography portfolio, visit his Instagram page.