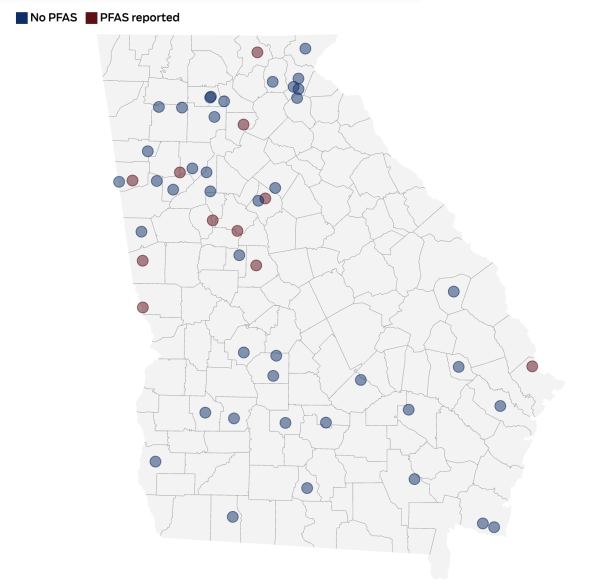

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency reported in August that 11 out of 52 county water systems in Georgia tested positive for concerning amounts of industrial chemicals. Two of those counties include Forsyth and Union County.

The chemicals found are defined as perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS for short. PFAS are found in stain resistant and nonstick products used in textiles and cookware. These chemicals are commonly referred to as “forever chemicals” due to the slow rate at which they degrade in the human body, resulting in PFAS accumulating in the bloodstream.

The effects of PFAS on human health are uncertain, according to the CDC. Animal tests indicate PFAS may affect reproduction, thyroid function, the immune system and the liver.

Two PFAS variants, PFOS and PFBS, were found in Blairsville well plants. The EPA reported 4.2 parts per trillion (ppt) of PFOS and 3.2 ppt of PFBS. Both of these amounts were deemed as significant. 7.8 ppt of PFBA, another PFAS variant, were found in well plants in the Cumming area.

Some UNG students attending the Cumming campus are aware of the threat of chemical contamination. Ty Tilley, a junior UNG student who frequently attends classes in Cumming, prefers bottled water over tap.

“I’ve always been pretty hesitant to use tap, but now I know that I need to stick to bottled water.” – Ty Tilley, UNG student

The United States Geological Survey found that PFAS are becoming prevalent in water systems all over the nation. Kelly Smalling, a USGS research hydrologist, said nearly 45% of tap water across the U.S contains PFAS.

“Georgia is definitely not a hotspot,” Smalling said. “We did identify hotspots across the U.S. Those tended to be in the Northeast, the Great Lakes area, as well and central and southern California.”

Despite Georgia being a less-affected state, researchers in the region see PFAS as a major concern. University of Georgia professors Gary Hawkins and Jack Huang are among those leading the charge to remove the chemicals from local water systems.

“We know it is a forever chemical, so we are trying to figure out ways to get rid of it within the treatment plants,” Hawkins said.

Hawkins and his team used various approaches for taking out PFAS, including using filters, chemicals and electric shock treatments.

“[With these methods] we are hoping to boost our treatment technologies.” – Jack Huang, Ph.D., University of Georgia professor

The EPA’s Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR5), the rule that helped find PFAS, was put into action in January of this year. The water sample collection period for UCMR5 will end in December 2025. Click here for more information.